21 | Writing Horns for Pop Songs

You’re a composer or a producer. You need horns arranged and played on your pop/funk/soul/R&B track. What do you do?

There are three options:

Hire a horn player/section. They’ll usually do the arrangement for you too.

Hire an arranger.

Do it yourself.

In most professional circles when producers or composers need horns they’ll book a horn player or section. That player will then fix (hire) the horns and write/arrange the chart themselves.

Sometimes, a dedicated arranger is called upon to write the charts. This can add more to the cost but might add an extra pair of experienced ears to your track.

The final option is to do it yourself. That’s what this whole article is here to help with.

Stuff You Should Know First

If you haven’t already, you should check out my articles on jazz harmony, voicings and horn ranges so this will all make sense. I’ll recap them a little as we go here, but having a good understanding of the principles will help a lot.

You’ll also need a basic knowledge of transposing instruments and notation. Transcribing and listening to a lot of horn arrangements helps immensely here too, especially if you’re not a horn player yourself.

THE HORN SECTION

Before we begin, I need to tell you a secret.

When we see classic horn line-ups on stage we often see 3 or 4 players. Usually a trumpet, sax and trombone with one player tastefully wearing a fedora or flatcap. This is a great sound live. Live sound gets muddied up easily and 3 or 4 horns are enough to give us the punch we need.

If you’ve ever recorded a horn section with great players, great mics in a great room, and then put them in the mix, you might have been disappointed with what might have been quite a thin sound. This is the same problem with sampled horns. Assuming this isn’t the sound you’re after, you might have tried to battle this with bus compression, EQ and saturation but the problem is often an arranging one - not a production one.

The truth is, in the studio, we rarely use just the sound of 3 or 4 horns. There are a few things that are very different to arranging studio horns:

We overdub an extra trumpet. The classic sound you hear on Michael Jackson, Earth, Wind & Fire and Stevie Wonder records is usually 2 trumpets, tenor sax and trombone. If you only have 3 horns, another trumpet part overdubbed makes all the difference for a bright, cutting sound.

We double the whole section. A bit like doubling a pop singer and hiding the double in the mix to add extra weight, we often track the whole section twice (or more) playing the same thing for weight and power. With 2 trumpets, 1 sax and 1 trombone, doubling the section gives us 4 trumpets for 2 saxes and 2 trombones - a very bright, powerful sound.

We add notes to chords. In a live setting, we only have three parts, in the studio we have unlimited potential parts (which is not always a good thing!). We frequently overdub 2 or 3 extra chord tones to fill out big chords and sections.

The players always play very intensely. The horns get pushed back in a mix so for a great sound, you need your horn players to play nothing less than loud and powerfully all the time.

I realise that last statement comes off as a bit unmusical, but unless everything is exaggerated - articulations, vibrato, note length etc. - you get a lifeless performance when put in the mix.

Legendary horn section arranger and trumpeter Jerry Hey has arranged and played for pretty much everyone from Earth, Wind and Fire to Dirty Loops. He pretty much defined the sound we’re talking about. His sound is characteristically trumpet-heavy. It’s brighter when compared to the usual trumpet, sax and trombone layout. To get this kind of sound in the studio, overdubbing or booking more trumpet players is a must.

A good thing to remember when recording horns is: ‘a whisper turned up is still a whisper; a yell turned down is still a yell’. The attitude and character the musicians play with translates across the whole track.

Assuming the room, players and mics are great, if we do these three things - overdub the trumpet, add extra notes in chords and have the players perform loud and intensely - you’ll get a sound like the classic records.

All this being said, that means we have to change our arranging based on whether the chart is to be played live or is being recorded. Just something to bear in mind as we continue.

LINE-UP

There are a few options when it comes to the exact section you want to use.

As for score layout, the players will just be given their parts (the ‘dots’) and no full score is needed, especially in informal settings. If there is a score, maybe for the arranger or producer, the horns aren’t in the same order as a big band. They still appear above the rhythm section but generally go in pitch order instead. Here are some typical horn line-ups for songs (in score order):

Column #1 is the most common live and studio setup. My preference is to use #4 in the studio for a bright, powerful sound but #3 also works well. #2 is also good live, but requires a good alto player to tune well with the trumpet.

Notice that in small sections, the trumpet is placed above the saxes in the score, unlike a big band.

UNISON IS YOUR FRIEND

90% of writing for pop, rock and funk tracks is unison or octave-based. The lines are usually made up from pentatonic or blues scales. This creates a clear, direct sound where the horns punch through the texture. Use octaves when you want weight or the range pushes one of the instruments too high or low.

With only 3 parts (usually trumpet, tenor sax and trombone) you have two options:

All 3 parts are in unison.

In octaves. This could be two on top and on the bottom line, or vice versa. Be sure you know how that affects the sound.

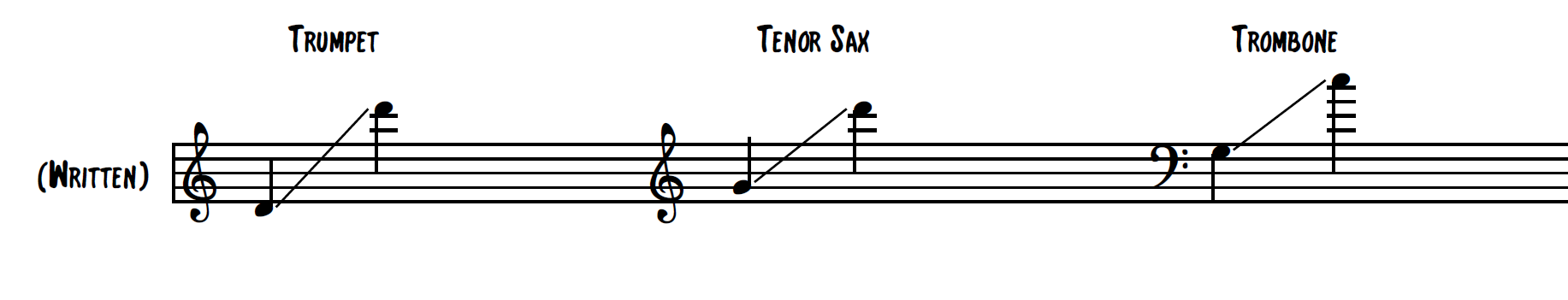

With all 3 parts in unison, you have to make sure you don’t go too high or too low for one of the instruments. For the clearest lines, you should have each instrument in the following ranges:

That means that if you want a line in unison, and you want it be comfortable for all 3 instruments, there’s a very small range where they overlap. Anything above or below this range could cause balance issues. I’ve called it the ‘Unison Zone’ because, hey, that sounds pretty cool:

Middle C to an octave above is the sweet spot for the trumpet, sax, trombone combination. Anything you write within this octave can be played in unison in a very controlled way. However, you can see it could be hard to stay in this octave for the whole track. The key of the track will also make a big difference. But what do you do if your lines go above or below the unison zone’?

Usually, you’ll end up splitting the line into octaves at some point. As a general rule of thumb for octaves:

Keep each instrument in it’s best range and the balance will work itself out.

This means that with 3 horns, you usually end up with two on the bottom line and one on the top, because tenor saxes and trombones can’t go as high as trumpets. This is a balanced sound and as long as you keep it comfortable for the players, balance won’t be an issue. Just be careful of having too many high instruments like trumpets and alto saxes doubled - it can cause tuning issues with less-than-great players.

Here’s an example of a very modern horn sound using mostly unison throughout (the straight 16’s split into 3rds).

The score is in C:

And here are the transposed dots - the ones you’d give to the players:

VOICING CHORDS

You want to use unison and/or octaves 90% of the time in your horn arranging so when chords do feature, they have a lot of impact. Here are the situations when you might break into harmony for effect:

After a unison/octave line you ‘cascade’ out into harmony for the end of the phrase.

Short hits or stabs are usually harmonised.

Pushes or sustained notes are usually made into chords.

Fast-moving lines don’t make good candidates for harmonisation in small horn writing.

When we do use chords, we usually use either close position voicings or drop-2 voicings. If you haven’t yet, I’d recommend checking out my article here on voicings where I go into it in detail. Here’s a reminder of the two:

Close position voicings are great for hits and stabs while drop-2 voicings are great at providing clarity and power in pushes and cascades. Ultimately, most voicing decisions will be decided by voice-leading, instrument range and balance.

To repeat myself, the most important thing is keeping each instrument in a comfortable range and giving them logical and satisfying lines to play.

If you follow this guideline, then the type of voicing to use is determined by the context. Any balance and voicing issues then usually sort themselves out.

If you check out the example above, you’ll notice that the trombone actually goes above the tenor sax in bars 9 and 10. Some trombonists prefer playing above the sax as they can play strongly in this upper register and the tenor still sounds great that low. Again, it’s all about writing in a comfortable range for each individual player, even though the parts cross.

When using chords, be careful of two things:

Dissonant intervals between the outside voices. The horns should feel complete in themselves. If you have a dissonant interval, like a minor 9th or tritone between your lowest and highest horn, it won’t sound great.

Resolving chords properly. This is an extension of my advice on voice leading. Make sure that all parts follow logical resolutions and voice leading. Sing/play through each part for awkward leaps and uncomfortable intervals. Each line should be great on its own.

Omitting Notes

Writing in three parts is much harder than four or more. In three-part writing, when you have a four-note chord like a Cmaj7, you have to leave out a note. In the studio, you could keep it in, but live you don’t have a choice.

The 5th is usually the first note to go as the chord still has it’s full quality. When we just have 1 3 and 7 in chord, this is called a ‘shell voicing’. The root can also go sometimes in favour of more interesting notes if needed.

Don’t forget that you can also substitute notes of a chord. The root can usually be exchanged for the 9th for instance. A full table of substitutions based on chord quality and chord tone can be found in my article on jazz harmony here.

Of course, if the option and budget is there - I’d always recommend 4 horn players to avoid having to deal with this all together.

PADS

One of the hardest things to arrange in my opinion are pads and beds with small horn sections. These happen especially in softer songs and it’s very easy to make the parts rhythmically boring. Getting the lush sound of a full band is also very hard with limited horns. It’s a bit like writing for string quartet rather than string orchestra - the colour of the ensemble completely changes into something more direct and is much thinner in small horn sections.

Pads can be arranged in close position, drop-2 or spreads and warm intervals like 10ths between the bass and middle voice work well. Be sure to keep each instrument in a warm register - usually on the stave (but at the upper end of the stave for trombone). A bari sax playing the bottom line down the octave is very common - wider intervals in the bass aren’t a problem and the bari sounds best on the stave or just below.

Here’s a simple example of 2 flugels and 2 trombones playing spread chords. This could have easily been 2 flugels, tenor sax and trombone, or with a bari too:

Supporting The Vocals

Usually in these genres, the horns are providing backing to vocal melodies. The horns shouldn’t double the voice as this restricts the singer. Horns are usually used for interjections and hits to fill in the space around the vocal melody.

Less is more - you should be able to sing the horn lines pretty comfortably and they should add spice to the arrangement, not the main dish (unless there’s a horn feature of course).

STEP-BY-STEP ARRANGEMENT

Now we’ve covered the basics, let’s have a look at a working method for writing these kind of horn arrangements, focused on the studio. I’m going to work with this 16-bar funk track:

Write the line

Let’s write a line on one horn for now, making sure it’s singable and not too complex. When listening to the track, and writing the line, here’s what I’m thinking:

The track is quite busy. There isn’t much room for a busy horn part so we’re going to mostly support the bass groove.

There are no vocals. The horns will therefore be quite prominent. Because the track is essentially 8-bars repeated, I’m going to change the horns in the second half for interest.

The build-up chords (Ab7, Bb7) would sound good with sustained horns pushing through.

The ending riff needs to have the horns on it too.

The chord progression is roughly:

| Eb7 / / / | / / / / | / / / / | / / / / |

| / / / / | / / / / | Ab7 / / / | Bb7 / / / :||

Also, check out the bass and organ grooves; you can see that the horn part pretty much writes itself. I often do this at the piano and write the line on a synth to the track, making a sketch of a lead sheet as I go. Here’s what I got:

2. Add phrasing.

This is one of the most important stages. I’ve now got my top horn line written down. I then try to match the phrasing exactly as I heard it in my head while also having it match the track. I’m doing this by making sure rhythms are accurate to the track, and articulations are doing exactly what I want then to. I’m listening for very specific things:

When do notes start and end? Especially the bass groove that the horns will be matching. Also, the organ part in bar 8 finishes very specifically on beat 3, so the horns will have to match this.

Long and short notes. The articulations have to match what is already going on for the horns to feel good.

If I have the session files, I’ll go into the MIDI here and see exactly how long the bass and organ phrases last. I’ll then decide how best to translate these to a horn section in notation.

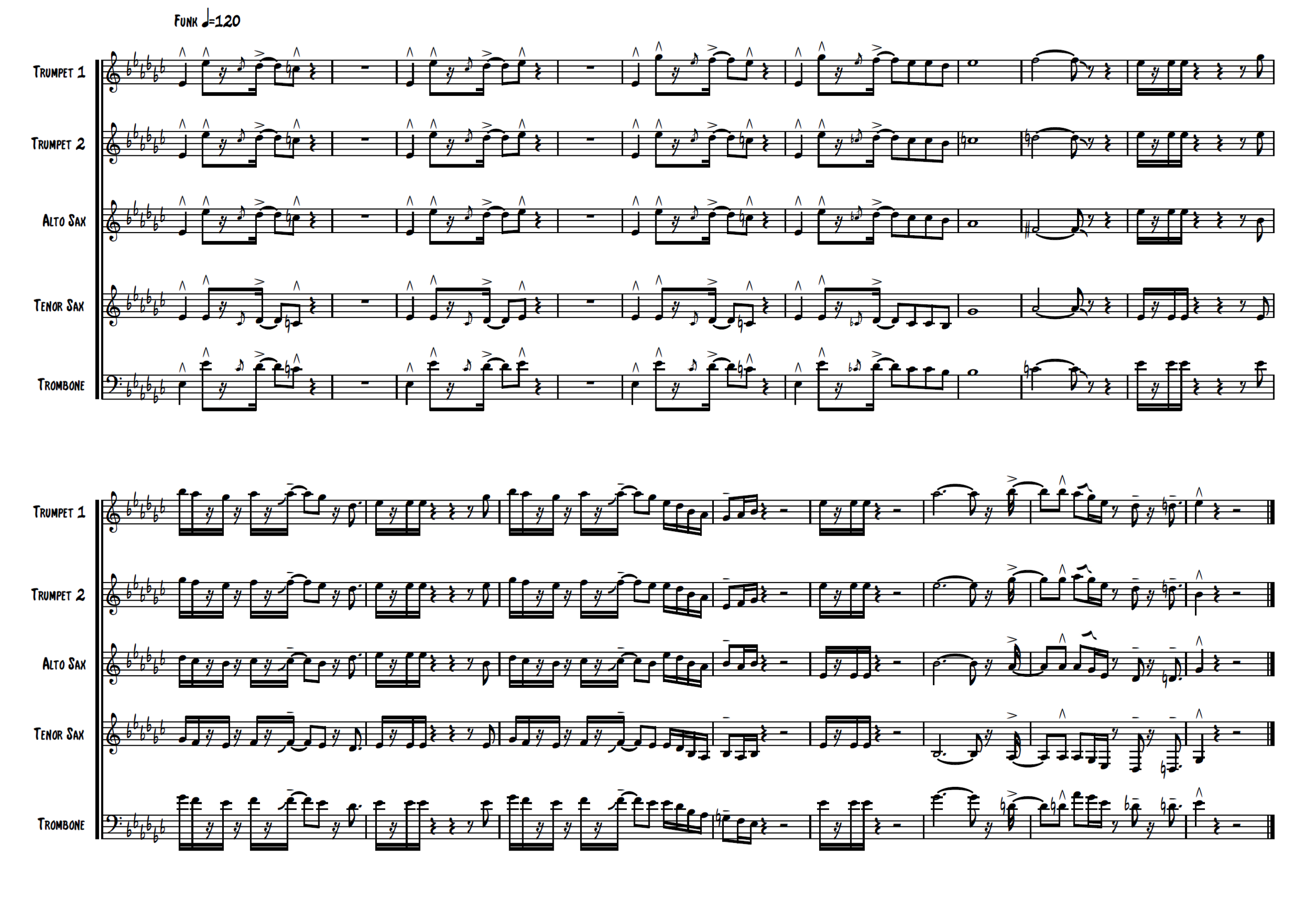

3. Fill out the other horn parts

I’ve decided to go with 2 trumpets, tenor sax and trombone for a bright, powerful sound. I also added an alto sax overdub for extra brightness. I’ve added the other 3 horns to the line now mostly in unison and octaves giving them the strongest range possible to play in.

As for harmony, I’ve used simple 3rds to begin with and then big chords in the pushes. (I’ve purposely tried to cram in as many voicing techniques as possible to show you what’s possible but a more simple approach would have easily worked here too.)

4. Record the horns

The next stage is tracking the horns. In a professional environment, you’re looking at a medium-size room.

In a pro studio, you’d expect to use Royer ribbon mics or Neumann U87, U47s or U67s. 67’s are the favourite of many LA sax players and 47’s, if you can afford them, are great for a classic LA trumpet sound. On a budget, any decent condenser will usually do - it’s the player that matters more.

In this example, I actually had the trumpets recorded remotely by Graeme from his own studio, I recorded saxes in my studio and Patrick tracked trombones from his studio too. I got the trumpet stems first and we phrased/tuned to them.

When tracking remotely or overdubbing separately, the order that you layer up the horns is really important. If this was an orchetsral context and we had strings for example, we’d want to start with the lower strings (basses and cellos) so the upper strings can tune to them.

The opposite is true in horn sections. We want to track the trumpet first. As the leader of the section, they’ll decide the phrasing and tuning. Everyone else can match them. It’s more difficult for them to determine phrasing and style if they have to match pre-recorded horns.

I asked for each player to double their part so we’d have the entire section doubled for a big sound, being careful to match the phrasing exactly the same so it all works together. In the double, I switched from tenor to alto and re-wrote the sax part a little, putting things up the octave to give support to the trumpet and add extra notes in the crunchy Ab7 and Bb7 chords.

5. Mix the horns

I won’t pretend to be a mixing engineer, but like most people nowadays, we usually have to wear a few different hats. Of course, the approach to mixing the horns changes with every track and context but I find when everything is recorded well, I find myself reaching for these tools most often:

EQ. High passing the lowest frequencies is always a must to remove mud. We work with at least 8 stems and the low-end noise builds up. I usually reach for subtle EQ on individual horns or linear phase EQ on the horn bus which can help remove annoying frequencies or add brightness/warmth.

Compression. Subtle compression used as ‘glue’ is a common feature on my horn bus. I don’t push it too hard and usually use the SSL bus compressor at a 4:1 ratio doing about 3-4db of gain reduction. The attack is usually quite late - around 10 or 30ms - to ensure the bite and attack of the horns remains. I find it best to go into each horn part individually and control the level of notes that stick out using automation (especially high trumpet) before it hits a compressor.

Saturation. Tape saturators and exciters can give the horn section a warm, cohesive sound and a little goes a long way.

On the final horn bus there might also be some reverb and limiting but this is all context dependent. Horns are easy to over-mix and start to sound fake.

Here are the final horns in the mix with the final arrangement:

REAL-WORLD EXAMPLES

Here’s a classic LA studio sound we got for The Wolf by The Spencer Lee Band. The horns are minimal but really tight. We tracked the trumpet up a lot and overdubbed the entire section:

LIVE HORN ARRANGING

When we work with a live horn section, we can’t double up the section and have to work with what we’ve got. Here’s an arrangement I did for Judith Hill’s The Pepper Club, in which we were going for a completely live horn sound. There are no overdubs and the sound is darker without loads of overdubbed trumpets.

You can see there are a lot more markings. This was to get the intention across quickly without the benefit of talking things through in a studio. I was more specific here than i would be in studio settings with my articulations.

FINAL THOUGHTS

To wrap up, let me just summarise my final tips for a good horn section arrangement:

Phrasing is king. Match the phrasing in your horn parts to your backing track and everyone will be happy, and it will sound great.

Use unisons and octaves most of the time - save harmony for impact.

Keep everyone in a comfortable, controllable range - the exact balance of upper and lower voices on an octave doesn’t matter as much as player’s being able to control their line.

When recording, overdub your parts at least once and try overdubbing the trumpet on it’s own on top of that again.

When recording separately, have everyone play, phrase and tune to the trumpet part.

When recording, keep the energy really high - anything not exaggerated will be lost in the mix.