11 | Voicings (Part 2)

We’ve covered the basic types of voicings and to be honest, most of the time they’ll make up most of your arrangements. But there are a few more niche ways of voicing chords to explore before applying it to a big band.

LOW INTERVAL CONSIDERATIONS

Before I continue, something of big importance is the issue of writing low intervals. I haven’t touched on this too much because I’m assuming a good working knowledge of some arrangement and orchestration techniques anyway. Just in case, I’ll bring it up here though.

If we write some intervals too low, the sound will be muddy. This goes for all genres of music. However, in big band arranging and in jazz we have to be extra careful. That’s because horns are timbrally very similar - we can’t count on their sound to clear up the texture. We also use a lot of tensions and putting these too low in a chord can unbalance the voicing.

Some resources offer extensive charts on exactly how low you can go with different kinds of intervals. For instance, an octave will sound good anywhere, you can use tenths pretty low, but a fourth too low will usually sound terrible. I think a big chart is probably overkill and I’d just offer one tip:

Below the middle line of the bass stave, make sure all intervals are consonant and ideally a 10th, 5th or octave. That should cover it.

It’s also worth mentioning now that notation software playback (and even sample libraries to an extent) just don’t deal with dissonance in the same way as a real big band. What could sound like a catastrophic altered chord in Sibelius, Dorico or Finale might actually be fine in real life - and vice versa. Trust your instincts and refer to other professional scores for similar voicings if necessary.

SPREAD VOICINGS

So far, we’ve been looking at voicings that are quite formulaic to produce, like four-way close, drop 2 etc. (Some sources even call them mechanical voicings). A spread voicing is a type of open voicing that allows for slightly more creativity. I’ll be dealing with them in five voices for now.

A spread is built from the bass note, rather than the melody note like we’ve been doing so far. They work great as beds or pads behind a melody and can offer a blanket harmony. Each note in a spread has a different function:

Don’t forget we can also substitute chord tones for more colourful ones, as long as they’re available. Here’s a few different five-part spreads for various kinds of F major chord:

Notice that the root note, F, doesn’t have to be in the lowest voice assuming that the spread is in the horns and the bass will cover the bass note. Voice-leading well between spreads is vital. Make sure the lines make good harmonic sense and follow conventional rules of harmony like having leading tones resolve upwards. No part in a spread should be doubled.

I broke some of my own ‘rules’ here - check out the Fmaj9(#11). The F to B interval at the top definitely isn’t consonant. But I was going for a more open, modern sound, stacked in fourths…

QUARTAL VOICINGS

So far we’ve been dealing with chords stacked in 3rds. In jazz, building and voicing chords in fourths is also very common. We refer to this voicing arrangement of stacked 4th as quartal harmony.

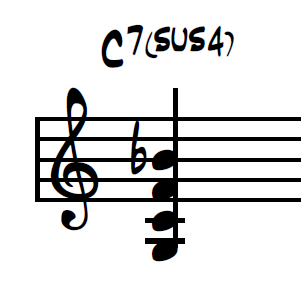

Some chords are inherently quartal. Take C7sus for instance:

The chord is automatically voiced in fourths. Some chords though, like a Cm13, can be voiced traditionally (tertially) or using quartal harmony.

Notice the lack of a 5th to clear up the thickness in the left hand. These constructions of root-3rd-7th in the left hand are known to pianists as ‘shell voicings’.

Quartal voicings don’t work particularly well in fast passages harmonising a melody. That’s where the tertial voicings in the previous article generally work better. The occasional use of quartal harmony on important melody notes, as background open voicings, or in modal tunes is often effective for a modern, open sound.

‘SO WHAT’ VOICINGS

Made popular by Miles Davies’ So What, a ‘So What’ voicing is a quartal chord with a major third on top. I could have used one above for the quartal Cm11 voicing:

The same considerations as when to use other quartal voicings apply.

SHOCK VOICINGS

A shock voicing is a collective term for voicings that are highly dissonant and there for effect, rather than as identifiable harmonies. They often use clusters, with tightly packed intervals rather than conventional chords. Using tritones, minor 2nds and other dissonant intervals are encouraged. Be sure to put each note in an effective range for the dynamic you want so it can be somewhat balanced.

You can play almost any cluster of notes you want for a shock voicing and ensure the top and bottom voice move by step into their resolution and it will sound good. I often focus on the target chord first and work backwards, creating a cluster with a bass note a semitone above my target note, and a melody note a semitone below.

Another effective way to get shock voicings is using altered chords or polychords, emphasising the available tensions rather than the chord tones and voicing them as close to each other as possible. This is also particularly effective with very dissonant polychords.

FREE VOICE LEADING

Free voice leading is also known by the Berklee crew as ‘line writing’. The process starts the same, you have a melody and then harmonise certain target notes. The remaining voices in free voice leading then do whatever they like, as long as they create interesting melodic lines for the inner parts.

The main benefit of this is that it’s the one of the only techniques that gives us contrary motion. Because it can create melodies that conflict with the harmony (remember, in free voice leading, melody is our primary concern), it’s best at fast tempos.

We’ve been concerned so far with making sure our harmonies support the key of moment, choosing which chord scale to use and effectively dealing with approach notes. It can be tempting to jump straight into harmonising using free voice leading as it seems free of all the ‘rules’ that we’ve encountered so far. The truth is it’s harder to be completely free with how we harmonise inner voices between target notes and still have it sound convincing.

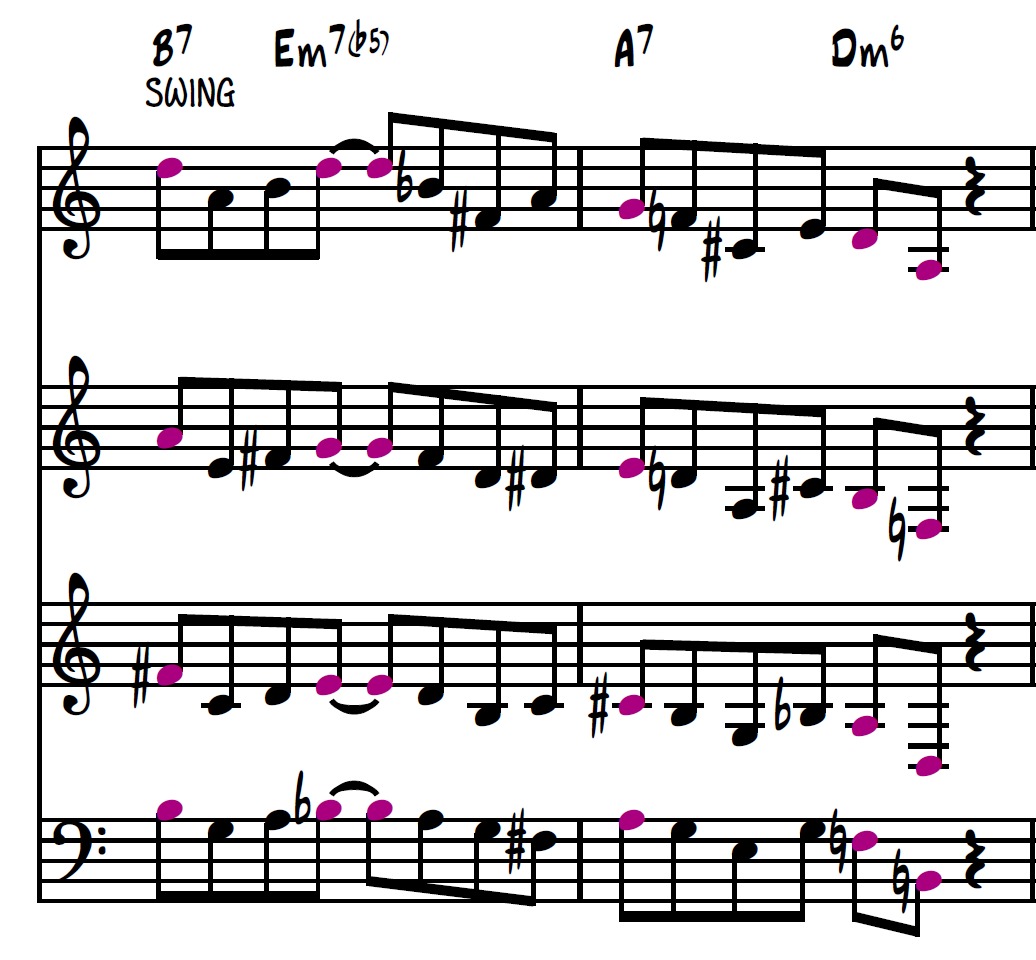

Let’s take this melody:

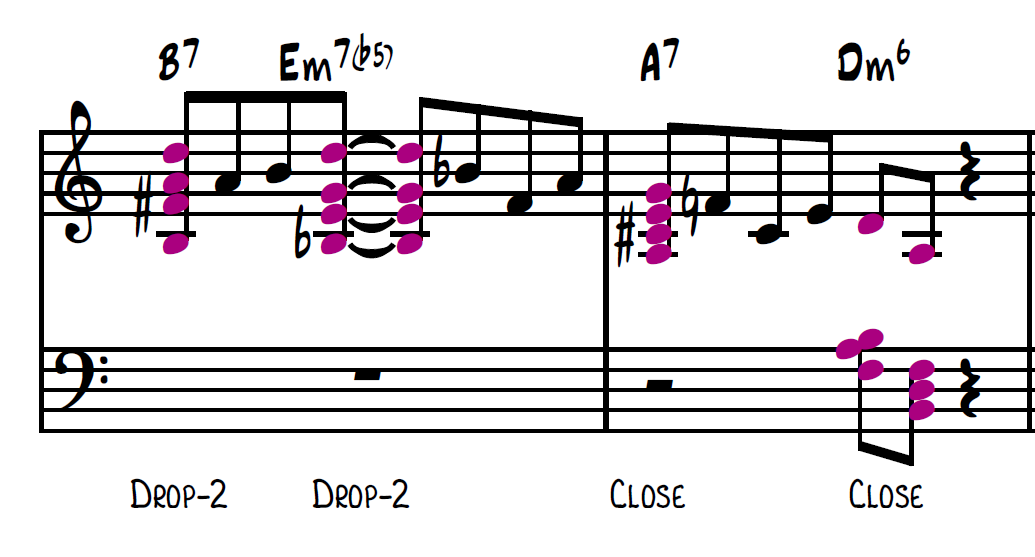

I’m going to harmonise the target notes in the usual ways, with close and open voicings. I’ve left the approach notes untouched for now. I could have done it in five voices, but I’ve chosen four:

Now let’s fill in the remaining inner voices freely, not worrying about whether they’re parallel approaches, dominant approaches etc. and just focusing on good voice leading while supporting the harmony.

Notice how the harmony is still largely supported, but the priority is having coherent lines and no repeated notes. The lowest line gets some contrary motion over the Em7b5. Good voice leading commands all here. If you play each line through, the last chord (the Dm6) isn’t as elegant as I’d hope for as each line has a bit of an awkward jump. You could substitute some chord tones in the last Dm6 to remove the tritone leap in voices two and four but in context, these are usually fine. The free writing technique can only get you so far.

This technique takes the longest time to become familiar with, and there’s more that can go wrong, but is a good tool to have for more creative inner lines.

CASCADES

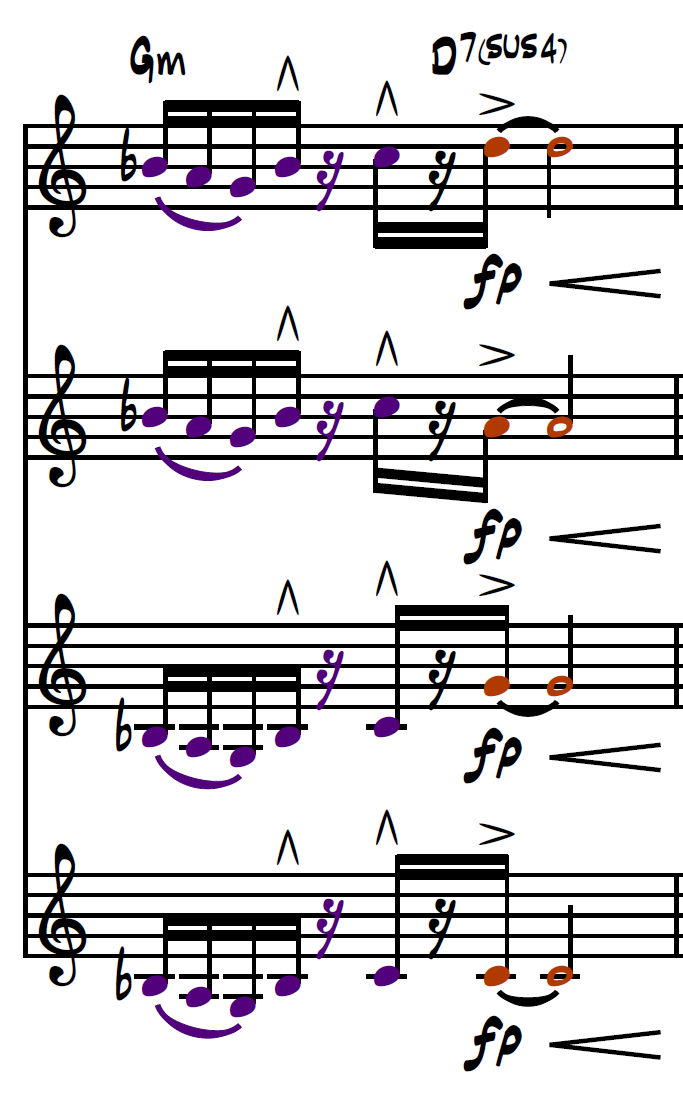

A cascade is a unison or octave line that splits into harmony. It’s most commonly used at cadences and is very frequent in big band and small horn arranging. A unison line creates clarity and then each voice ‘cascading’ into harmony creates an expansive, powerful effect. The purple notes show the unison line (these could easily be octaves instead) and then the orange notes show the four-way close voicings they cascade into.

Notice in the first orange chord I substitute the 5th (F) for the #11 (E) to avoid a repeated note and create a more satisfying line to play.

Care should be taken at which point the cascade should begin and in which voices. The unison line can become unbalanced too quickly. It’s usually best saved for the final punctuation of a phrase. If you do it too early or in an unexpected place it can throw the phrase off balance and ruin the effect.

Here I cascade on a relatively unimportant offbeat eighth note and it sounds like the first few notes in unison were a mistake. Plus, the repeated note in voice two doesn’t help make it a convincing line!

Cascades are used very frequently in small horn writing when arranging horn backings for funk/soul/r&b tunes. These are often done with sus4 and sus7 chords:

TWO- & THREE-PART VOICES

The eagle-eared (do eagles have good ears?) will have noticed I seem to have skipped over two- and three-part voicings. This is intentional. 2-part voicings, if not unsions or octaves, are usually a simple harmony like a 3rd or 6th, more rarely a 5th or 4th. It seems self-explanatory to most arrangers that this option exists. It’s quite common in older charts and when the texture needs to be thinned out. I’ll talk about it’s use more in the next article on unison and octave arranging.

Three-part writing is among the hardest in jazz. You don’t have enough voices to make extended chords fully realised while maintaining good voice leading all of the time. Outside of the small jazz combo, it’s not too much of an issue. Big band writing is rarely ever three-part.

The one situation where it comes up a lot is in the funk/soul/r&b/pop horns where you might have a one trumpet, one sax and one trombone. Fortunately, the harmony is usually less complex so there’s less chord tones and tensions to represent. Unison and octave writing is also very common in this style. However, it still provides its own challenges. I often try to get an extra horn added, usually a bari sax or another type of sax, or at least overdub another part. It saves some awkward leaps in the other horns and I often find the middle voice (alto or tenor sax) is pushed too high or too low most of the time for chords to balance. I dedicate a whole article to it here.

For now, that’s everything I think you’d need to know about jazz harmony and voicings and we can get on to some actual arranging.