7 | Articulation

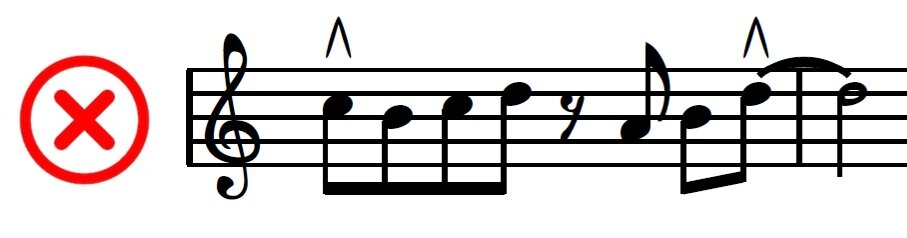

What's the biggest tell-tale sign of a non-jazz musician arranging jazz? Other than perhaps the infamous 'dotted-8th-note-16th-note' swing pattern, it's probably the use - or misuse - of articulation.

Ignoring harmony, form and the eye-sore of a font that is Inkpen 2, the most immediately obvious symbols that tell you it’s a jazz chart are the liberal use of articulation markings. Getting these wrong shows a player at first glance they'll have to figure out the phrasing on their own and that the arranger does not have their back. It would be synonymous with turning up to a session and seeing an orchestral score place the strings above the brass - no matter how well it's orchestrated, it's difficult to be taken seriously when the stylistic fundamental are so wrong.

The good news is that the articulation used by jazz musicians, and by extension in genres such as funk, R&B, soul and pop, is fairly standardised. Arguably more standardised than the same symbols in orchestral scenarios where the players, orchestral default and historical context can play havoc with the most well-intentioned placement of articulations. This fairly rigid standardisation of markings makes it easy to learn and implement. Of course, in any genre, a precise translation of ideas to notation is impossible, but indicating intention with these symbols is the closest we're going to get. These explanations will deal mostly with horns first. The rhythm section generally follows the same set of rules but I’ll be using horns here.

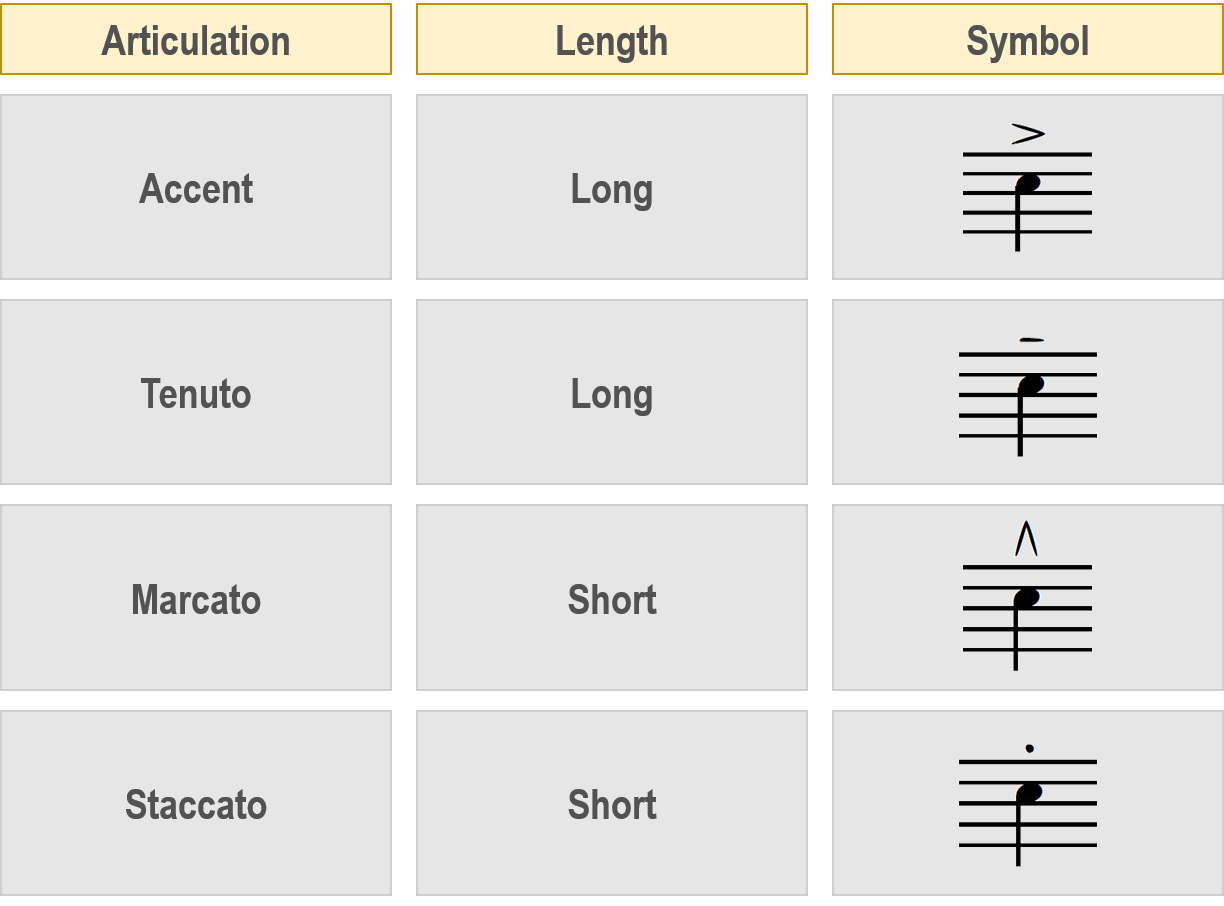

Symbols and markings can be split into two categories:

Markings that affect note value

Markings that create a special effect

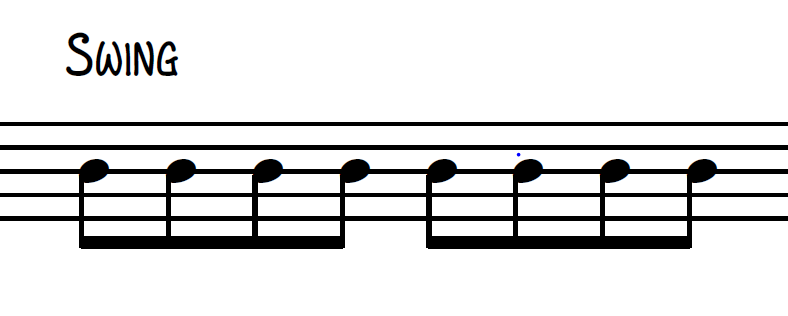

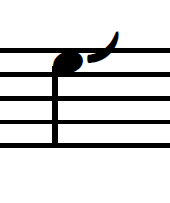

Note value and the character with which notes are played are really important in all styles of music - big band charts are no exception. One of the most common ways of playing is swing. Swing by default applies to 8th notes, but can apply to 16th notes if specified. Swing is a very personal thing to jazz players. The amount of swing you use and the ensemble you achieve when everyone is locked together aren’t things that are learnt easily, and really can’t be notated. Saying that, swing is heard most accurately as this rhythm:

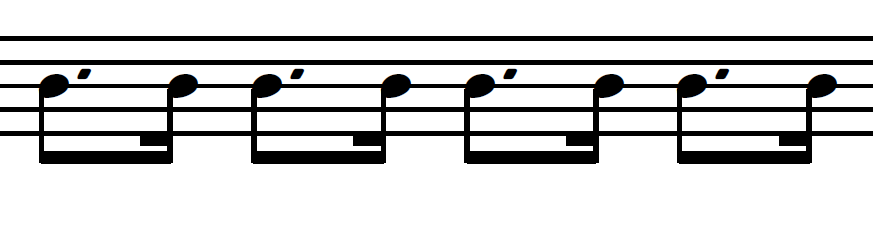

And notated like this:

But never like this:

The alternative to playing swing is straight - as you’d usually play, with each quaver taking up the same amount of time. Other variants such as shuffle, like swing, are best written as the word and with 8th notes.

With that covered, before I list the markings that affect note value, there is a very important concept at the heart of jazz and other popular styles that underpin everything to do with phrasing and articulation in this style of music.

LONG-SHORT PHRASING

Jazz, especially swing, works because of the long-short phrasing of notes, i.e. playing some notes longer than other notes. Here, I call this style of phrasing the ‘long-short’ rule (knowing full-well how controversial the word ‘rule’ is, especially in jazz, but hey, it sounds less pretentious than ‘tenet’ or ‘guideline’. You’ll find plenty of exceptions to the following of course).

The relationship of the short note to the long one determines the degree of swing - the longer you wait to play the short note after the long one, the harder you swing. It goes without saying that at faster tempos, this swing starts to straighten out. This principle of long-short extends throughout all of jazz phrasing and greatly depends on note value. There are two important aspects of the long-short phrasing rule in jazz:

1/4 notes are played short, unless marked long.

1/8 notes are played long, unless:

Marked short

Happen just before a rest

Have another 1/8th note before them and are on an offbeat.

I realise that this seems conditional and not too useful. A better way of internalising the long-short rule is by listening. Here is an example of a line and how it would actually be played:

Notice that even without any articulation markings, there is a sense of swing and phrasing. It all depends on where the note falls in the bar.

One of the most common rhythms that catches people out is this:

You’d expect the 1/4 note to be held for full length in most other styles, but here, following the long-short rule, the 1/4 note is played short. There is no need for a staccato dot on the 1/4 note, and no need to write it as an 8th note instead.

This principle extends to other styles of playing, even genres traditionally played straight like funk. In these cases 16ths might be swung instead of 8ths, or everything could be played straight, but it would be common for the players to put just a very gentle amount of weight onto what would be the long notes if it were swung to make it groove. This is automatic and nothing needs to be written to make it happen - they just follow the long-short phrasing rule.

One rhythmic anomaly to this rule is a series of staccato quavers. Even with a swing indication, these would be played straight:

To switch between Straight and Swing feel, you can do either of the following (but doing both would be redundant):

I usually use the first option when it’s just a few notes, the second when it’s a bar or more.

Overall, the long-short rule preserves the groove of the music: markings shouldn’t contradict the natural phrasing without good reason, but should usually enhance and clarify it.

MATCHING THE PHRASING

An important note should be mentioned here about phrasing. Players will generally look to match the phrasing and articulations of others around them, or if they’re playing to a backing track in a recording session, whatever that’s doing. This is of course the case in all genres, but as every instrument of the ensemble in a big band is capable of very precise rhythmic precision, it seems the attention to this kind of detail is enhanced. If the arranger doesn’t take this into account with the articulation markings and note values, a lot of questions are raised. I’ve been guilty of this, especially when starting out, and it wastes a lot of recording time. Check out my article on the importance of writing matching phrasing/articulations here.

It’s also worth mentioning here that by default, when horns see a long note, they’ll put a slight fortepiano crescendo on it (fp<) without you asking. You can of course write one for a very obvious effect. Giving this indication to guitars, basses and pianos is of course redunant.

The Default Articulation

By default, horn players will play notes detached or tongued. Every orchestration book says this, but what does it mean from a technical standpoint? Usually books just say something like ‘the player says the word “tah’”’ and call it a day. The precise way in which the embouchure creates the detached articulation is fundamental to an arranger’s approach to big band articulation.

On a sax, you get sound by breathing into a mouthpiece with a reed attached. This reed vibrates and creates sound. By resting your tongue on the reed, you stop the vibration and stop the sound. Sax players (and clarinet players for that matter) blow air through the instrument with their tongue resting on the reed at all times. They then release the tongue when they want the note to sound, giving a nice clean start to the note.

Trumpet and trombonists start the air stream, but keep their tongue against the roof of their mouth. To make sound, they release the air by saying the word ‘tu’. This, unlike the sax or clarinet, means no air escapes the mouth before a note is sounded. There’s more variation with brass articulation technique in general, and it can be quite a personal thing. It’s also something often mis-taught and burgeoning brass players often have their entire technique reworked after many years of playing!

Without any markings other than the notes themselves, unless too fast, horns play individual notes this way and give a clean, detached start to each note. This is the default, and this phrase is ‘tongued’:

Legato

The opposite of detached playing is legato and is a familiar marking from most orchestral scores. The legato slur indicates smooth, continuous playing in one breath, with no tongue stopping each note. If you're looking for a precise funk sound or swing, using legato anywhere other than in passages too fast to tongue would be seen as counter-intuitive. In fact, you see a lot less of it in jazz charts than you do in orchestral scores. This is because of the important rhythmic nature of swing and long-short phrasing gets blurred when not tonguing each note separately.

It’s usually best, in a big band setting, to write notes detached and let the player slur it as they see fit, unless it’s integral to the phrasing of the line, or something like a ballad that would only make sense slurred. (Trumpets for instance, when they play melodically in the extreme highs of their range wouldn’t necessarily be tonguing every single note, but it would look strange to write a legato slur over all the notes.)

With the long-short phrasing rule and default articulations in mind, let’s look at articulation markings that affect note values first. These apply equally to horns and the rhythm section.

MARKING THAT AFFECT NOTE LENGTH

We can split markings that affect note lengths into two types:

Short articulations

Long articulations

Exactly how long or short is a relative thing and will be determined by the tempo and context. Clipping a note too short in a ballad will sound strange and players will look to the Lead Trumpet to know exactly how and when to phrase.

Accent

The accent is a familiar marking that in jazz means something quite close to our accepted common use. Players in a jazz context will play with more attack and weight behind the note as they would in any other setting, but in jazz contexts, the accent is a long articulation. This means accents on notes will be given their full value (and in certain contexts even a bit more). It shouldn't be used in contexts where the phrasing would imply a short note by the long-short phrasing rule, and definitely not on short notes themselves.

What makes this a bad example for accents? Well the first 8th note is on the offbeat so is a short note when swung. The accent is a long articulation so holding this note long will ruin the swing feel. It looks strange. The same goes for the other 8th notes in the bad example.

In the good example, accents are on notes that are already long so fits the swing phrasing much better. Notice that the 8th notes just before the accents are clipped short while the tongue prepares for the added power and emphasis needed for the accent. This space before the accented notes also helps them have more impact. Be sure that’s what you want before you write an accent.

Marcato

Marcato is more commonly used in jazz arranging than it's orchestral counterpart and has the same role as an accent, giving more attack to a note. The marcato however is a short articulation, and shouldn't be used on notes that would usually be played long. Marcato is the jazz arranger's articulation of choice when incisive, sharp attacks are needed on very short notes - not the accent marking. Also can be called a ‘hat’, ‘cap’ or my favourite; ‘teepee’.

The bad example uses the marcato on long notes. In swing, an 8th note on the 1st beat of the bar will always be played long and the marcato contradicts this. In your mind, replace the marcato with a staccato dot and see how strange this passage would look when played swung.

The good example uses the marcatos on short notes so just tells the player to really emphasise these while keeping them nice and short.

Staccato

Staccato means the same in the jazz idiom as the orchestral one - a note played short. It's less common though, as most of the time the short note will be automatically played short by the long-short phrasing rule or, if a marking is needed, it will need the attack that a marcato articulation provides. In jazz, the staccato should only be used for notes played very short while keeping them from standing out of the texture.

The bad example here isn’t that bad. The first two 1/4 notes would be played slightly short anyway because of the long-short phrasing rule (1/4 notes are played short). The 8th note with a staccato dot is just a bit clumsy to play because when swung, this 8th note would be long. Cutting it short looks and feels strange.

Tenuto

Seeing a tenuto marking will ensure the player provides the full amount of weight and length to the note. Tenuto is a long articulation. It can be used to clarify the long-short phrasing by placing it on longer notes or to extend the value of short notes (although this isn’t as common). It shows where emphasis needed.

The bad example here effectively ruins any sense of swing or phrasing. By emphasising and lengthening the offbeat notes, you end up straightening the line out and it looks very strange.

Tenuto can be used to lengthen crotchets that would otherwise be shortened by the long-short rule:

So far, here's a summary of the markings that affect note length and how they're to be used:

The staccatissimo wedge isn’t used in jazz arranging:

Some combinations can be used, providing they don't contradict one another with regards to being a long or short marking. For example, in this style, a marcato and accent marking would be nonsensical, (you’d be telling the player to play short and long at the same time) as would the usually common combined accent and staccato marking, (here you’d be indicating the note should be accented, long and short). Here are the three combinations you shouldn’t use and, and one that you can use (but is a bit redundant - just an accent would do the same thing):

MARKINGS FOR SPECIAL EFFECT

Moving on from markings that affect note value, these are the markings that create special effects. Some of these effects are less standardised and more specific to jazz and popular styles but are common tools at the arranger's disposal. I’ll focus on how these affect horns for now.

Glissando

A familiar symbol, a glissando can happen at varying tempos and are most commonly up to a target note, or connecting two notes together:

Glisses are commonly written without start or end notes. Like grace notes, it's assumed glissandi in this style are played before the beat of the target note.

The length of the gliss is determined by context or verbal instruction and I don’t bother writing the word ‘gliss’ over the line unless adding a verbal instruction like ‘big’ or ‘small’. You can use a squiggly line or a straight line for glisses which both convey the same effect. I prefer the squiggly one for big band charts.

There are a few technical considerations when writing a glissando:

Sax

A gliss on the sax is created using the keys and playing a fast scale that is usually chromatic, but can be diatonic depending on context, especially if the music is slower. Here are a few considerations that are sax-specific - it goes without saying that for all these problem areas, pros will make it seem easy.

A gliss down from written low D doesn’t leave much room at the bottom of the range and involves some awkward fingering as the sparsely-used pinky fingers have to be quite active to make it smooth.

Glisses between written high D and high F# are possible but can sound a bit clumsy as the notes are all usually accessed with the left hand palm.

There will be a change of colour when writing a glissando between written C# and D. This is where the saxophone’s break is to be found. C# involves no fingers pressed down, whereas D involves nearly all the tubing closed. The colour of C# is brighter than D, but good players can mask this with embouchure and alternate fingerings for both notes.

Trumpets

Trumpet glisses are created by playing a chromatic scale from the starting note to the target note. The valves are not fully depressed (known as ‘half-valving’) and lip tension is increased or decreased depending on the direction of the gliss.

Other techniques can be added to the gliss for cool effects on trumpet, like bending the top note away from the general direction of the gliss, or ending the run on a half-valve and an indefinite pitch. All glissandi are possible on the trumpet, but generally avoid the unfocused low register up to about middle C.

Trombones

Trombones use the slide and lip to create a glissando. Trombone glissandi work best when the notes are within one, unbroken slide. If unsure, checkout a slide position chart, or just write a gliss into the target note and leave it to the player to find the best position. On a tenor trombone without an F trigger, the only notes that are impossible to gliss into are the two that are found only in 7th position:

Fall

A fall, or fall-off, involves playing a note and then a rapidly descending set of notes after it. It’s notated with a descending curve after the main note. It’s commonly paired with an accent, but not really marcato as playing super tight and short and also doing a fall is a bit counter-intuitive. The length and range of the fall will be determined by the Lead Trumpet as will the exact style of all these articulations.

For a fall, sax players play a rapidly descending scale. Trumpet players use either the lip, valves or both depending on the range and length of the fall. Trombones use their lip for high notes and introduce the slide as the note gets lower.

If you want to add an accent, regardless of the length of a note, an accent rather than a marcato should be used for all falls and glisses. Falls can be short or long:

Scoop

A scoop is a lip slur from about a half-step below into a target note. It’s pretty quick and is notated with an ascending curve before the target note. The target notes can be long, short, accented and with marcato.

Saxes and trombones are usually better at pulling this off than trumpets. Saxes use their lip to bend into the note and trombonists use their lip and/or the slide for a mini-gliss. Trumpets use the lip so can struggle if the note is written too low where the harmonics are farther apart. In fact, if it’s too low in any of the horn section it won’t be pulled off completely successfully. At the very least, avoid the bottom 5th of saxes and trombones and the bottom octave for trumpets for this effect.

Bend

There’s a lot of room for interpretation in this effect. The symbol is a little ‘u’ shape curve above a note, indicating that the note should be brought down in pitch and then back up. The note value it’s put on should be long enough to be able to do that in, but some really cool effects can be found when using it on short notes too. It’s a very tasteful articulation that often happens instinctively, coupled with a slight vibrato. Again, if the note is too low on any of the horns, where the partials of the harmonic series are further apart, it makes it more difficult to pull off. Follow the advice on register for scoops above.

Shake

A shake is a rapid kind of tremolo effect which sounds kind of like extreme vibrato. Trumpets move quickly between the target note and the next highest partial in the harmonic series by default, but you can ask for a ‘wider’ shake if necessary.

Saxes generally play a diatonic pitch above the target note as a tremolo, or play a trill, and trombones use their lip for the next harmonic partial. Of course, the higher for brass instruments, where the harmonic partials are closer, the easier it is. Shakes can be long or somewhat short, and can be started halfway through an already ordinary note, like vibrato.

Doit

A doit is a rapid gliss away from the target note up to an indefinite pitch. It’s written like a fall, but in the opposite direction. Trumpets and trombones will generally increase lip tension to ascend through the harmonic series, possibly using the valves/slide depending on the range. Sax players will play an ascending chromatic scale. Make sure the note isn’t too high or they’ll be nowhere to ascend to!

Turn

A turn is a familiar ornament and is applied in jazz and pop settings in a similar way. The jazz symbol is a little different to the traditional classical one though. It’s usually played diatonically. Turns are possible nearly everywhere on all of the horns apart from in the extreme low registers. Saxes and trumpets can run into awkward fingerings and trombones can be asked to jump between slide positions really quickly the lower they go so check fingering and slide position charts if it’s a low turn.

Also called a ‘flip’, the turn is notated and played as follows:

Plop

A plop isn’t widely used and crops up occasionally - in fact I thought about omitting it - but for the sake of being a completionist, here it is. A plop is a rapid descent onto a target note from above. The notation is the same as a scoop, but coming from above instead.

Ghost Notes

Ghost notes aren’t used very commonly in most charts except in guitar and bass parts where it’s a specific technique and is written more commonly. They’re also often found in transcriptions of improvised solos for a lot of instruments. I like using ghost notes to show the feel of a phrase, and find them especially useful in funk to show notes that shouldn’t really be heard, but felt. The player will do this naturally, but in a recording situation it might be the difference between a 1st time read-down and a second.

Growls and Flutters

Used usually only when soloing, growls and flutter-tongues are special effects that use the throat and tongue respectively to create aggressive sounds. Trombone glissandi with growls aren’t uncommon, and are especially common in older styles, along with trumpets often coupled with mutes for special effects. I wouldn’t recommend symbols for flutter-tongue or growls in jazz charts although sometimes, traditional flutter-tongue tremolo lines are used. It still usually raises questions and I’d usually ask for growls with text instead. Writing ‘growl’ and a line indicating the affected notes is usually fine:

Sometimes, for trombone and trumpet, you need to indicate open (o) and closed (+) plunger positions while growling. Instead of text here, traditional flutter-tongue tremolo lines would work too. You can also do this without the growl too. I’d recommend the following notation:

Subtone (Saxes Only)

Subtone is a breathy, smoky sax sound used in the lower register, especially on tenor saxes. It involves taking less of the mouthpiece in the mouth and is a relaxed, undefined sound. It used to be a common technique but is somewhat dated so is more appropriate as an ‘effect’ nowadays. You just need to write ‘subtone’ under where you want it to begin, and if context doesn’t make it clear when to stop, a marking such as ‘ord.’ or (better for jazz) text such as ‘normal’ should work fine.

Over-Marking

My final thought on the topic is that of using too many articulations. The more you use, the more risk you have of interfering with the long-short phrasing rule, or repeating information redundantly that would be played by default. You can also easily play a game of ‘boy-who-cried-marcato’ if every note is accompanied by a symbol - they’ll start to lose their effect and start to be ignored. Saving them for exactly when they’re needed or to contradict the default is the best use, but in a recording situation, or with an unfamiliar group, it doesn’t hurt to clarify your intentions for the way things are phrased.